This is an edited version of a talk delivered on September 10, 2022, to the Calvary Bereavement Counselling Service ‘Living with Grief’ seminar. It also appears in the Good Grief! September newsletter.

I waved my nephew Christian off recently, as he drove back to his home in Tamworth, in country NSW with his wife, Jenna. They stayed for a week and there were some unexpected conversations. Yet why was I surprised?

They’re a happy young couple with their life ahead of them. But we wandered into grief territory. Christian was, after all, right at the centre of our family’s sorry business, when it hit us more than 10 years ago.

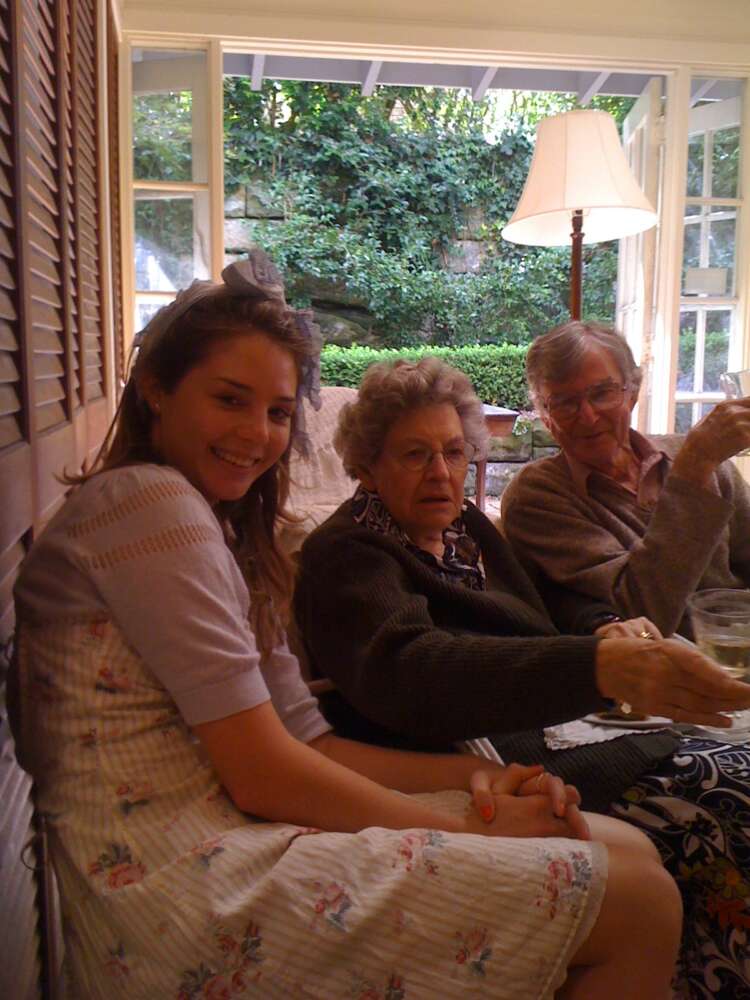

My mother, Christian’s grandmother, died an expected death in old age and when she died our family grieved.

I learnt from that that what we know about grief, even what we know about dying, is not static. Our knowledge changes and develops all the time.

So we need to be wary of ‘rules’ and ‘expectations’. These are more culturally defined than we often realise.

There’s a saying from the US army: when you have the coordinates of the map in front of you but you see a valley instead of the mountain marked on the map, it’s not the topography which is wrong – but the map. In other words, the books and the papers and the authorities aren’t always right. Especially about matters of the heart. That is true with grief too.

There’s a saying from the US army…it’s the map that’s wrong, not the topography.

As Mum got closer to death, my siblings and I were all very afraid. That led to anger and fights, which I later found is very typical. Sound familiar? Guess what percentage of families one study found were impacted by this? 100 per cent. This is one of the main reasons it’s so important to explain more about death and grief to people.

If we know more, we’ll be less afraid and this will mean less anger and regrets as we grieve.

Despite the chaos and confusion that our sibling misunderstandings caused, we managed to pull together, something that I felt was orchestrated by Mum, one of many mysterious elements to her death.

So there was growth and strengthening, delivered by this death in unexpected ways. It showed the possibilities of post-grief growth. This is not to say that death and loss are good. But that growth is there for all who grieve, if they want to accept its possibilities.

However, pain and suffering at someone’s death can compound the grief of those who must sit and watch it. A bad experience like this can contribute to the grief you feel over the death of the person you love.

Notice I say love, not loved. We don’t stop loving someone because they died. And this way of looking at grief over death is now more accepted too.

I resigned to write about Mum’s death – then I was blindsided.

Dealing with all the aspects of Mum’s death was a very big, extraordinary experience. But then, eight weeks later, we were blind-sided.

I had resigned from my job as a newspaper reporter on the Thursday to write about her death and then the following Saturday my brother Julian was killed in a motor-cycle accident. He was 50 and he left a widow and three children behind, aged 17, 14 and 11. That 17-year-old was the Christian I mentioned before.

Two deaths in eight weeks. But two deaths so extraordinarily different.

The grief over Julian was very unlike the one over Mum. This one was wild and woolly. His death was such a shock, so unexpected. The circumstances were brutal. A young, 17-year-old driver ‘T-boned’ him as she drove into his motorbike on a country road, coming off her private drive.

The grief over Julian was very unlike the one over Mum.

When Mum died, I felt as though I gradually emerged from a cocoon, back into the ordinary world. But I remember when Julian died being unable to comprehend how the rest of the world was going on, just as usual. In the first little while I found laughter strange. I felt insulted by people who enjoyed themselves and joked – including those at the Tamworth Country Music Festival, which was on at Julian’s hometown at the time he died.

We accept today that death doesn’t end our relationships. Those giving professional support are more inclined to encourage the person to engage with the feelings in ways that allow life to come back, in new ways. So we don’t aim to eliminate the grief but to help people heal around it.

New research is more respectful of the grief of the elderly too – although this field has not grown as much as it could – there’s so much more work to be done in this area. As we age, we accumulate many griefs. How does this impact on us? And why should our grief just be dismissed because of age – which it often is.

We grow until the day we die.

I would urge everyone, even if you are defined as ‘elderly’ to ask for professional help when you need it, to manage your experience of grief. Whatever age you are, you still have the right to feel supported as you grow. We grow until the day we die. Do not see the resources spent on helping this growth as wasted.

Again, coming back to more immediate grief, common questions and concerns are “Is this normal?” or “what will I feel next?”, “when will my grief be over?”

Grief can last for days, weeks, months even for years. For everyone it will be different. But be careful. Is the grief you are experiencing holding you back?

Whatever age you are, you still have the right to feel supported

Grief is not just an emotional experience. It can have an effect on our thinking and the way we focus.

Sometimes people are frightened by this or what seems to be a loss of awareness.

Remember, in raw, new grief, our minds are trying to make sense and incorporate loss. We are often quite shocked. Our brains narrow down and jettison information which doesn’t help us with that, so we can be forgetful, disoriented and bewildered.

To be in that state is okay. But be careful. Consider whether you have become ‘locked in’ to that state.

Guilt is also connected with grief. “I wish I’d said more.” Or “I wish I didn’t say that.”

Christian became a school teacher, just like his father. And we chatted about that. He sometimes doubts his commitment to that but feels he shouldn’t change because his father was a school teacher.

So when Christian stayed, it was important to remind him: “Your father would want you to grow. He would not want you to stay in teaching just because he did.”

Helping to create community by being that community.

Helping to create community by being that community for others is important. Is a woman at your golf club grieving the loss of her husband? Don’t avoid her. You are what and who she needs, even if you are incidental to her life.

In fact, when people are grieving they can be hyper-aware of people around them, even though solely focused on the person they have lost. Ask if you can sit with her and chat with her, if you would ordinarily do that.

We turn to our communities to cope with grief but sometimes this is not enough. That said we need to make sure that we are the community that our grieving can turn to.

About that urge to ‘fix’ grief.

When someone is grieving, we can feel the urge to ‘fix’ it. But the reality is we cannot ‘cure’ somebody else’s grief – although we can certainly support them.

For friends, and family what we can offer is a willingness to sit there, held in the grief with them.

“How did his death have an impact on you?” “Do you want to talk about it?” or “I will just listen” (and to mean it.)

And we don’t have to say much, just a hug or one kind word can be enough.

One grieving father, who’s young son had died explained that he needed friendship at the time but not talk. So he was comforted most by those who offered to sit with him but then say nothing.

It is okay to ask if we can help those who are grieving, even if this is rejected. People are usually grateful that you tried. What hurts more is being ignored by others, especially whole groups, pretending that nothing has happened.

If each individual’s grief response is different, with that comes the understanding that the support that we need will vary from person to person. Not everybody needs to talk about their grief.

Where once people might have insisted you talk about it, today the professionals might say: “If not talking is better for you and suits your personality more, what are the other ways that we can help you?”

You might be guided towards a way of expressing your grief that suits your personality more, for example, by writing, journaling or drawing.

Getting help to live with grief.

Often, we don’t realise we need extra help until our families say something. So people will say to their counsellors “Look, I think I’m okay but my family don’t.”

The importance of direct individual counselling is that it creates safe spaces where people with training can help us explore our grief.

As I mentioned before, this won’t ‘cure’ or ‘fix’ grief. But support services can help us develop strategies to both keep the person we’re grieving close to us, but to move on at the same time.

As my grief over Julian softened, which it eventually did over the next year, it felt like disloyalty.

Newly bereaved people often see no point in moving on or letting go. Often, they don’t want to. When I knew I was moving on from my grief about Julian’s death it felt to me as though I was going to lose him all over again. But when I finally let go of that grief, I found it didn’t mean that I had really lost him at all. I found other ways to honour him.

For me it’s by writing. For others it’s to plant a garden for the person, or to fund a memorial prize at their school, or to cook his favourite food every birthday. There are many ways we can find to move on – without forgetting.

Support services emphasise this much more today. Their goal is often now to help the person endure the changed relationship to the person who is not here with us.

I come back to Christian. He is now 28. During his stay he asked many questions about his father. He wanted to hear more stories about him. I retold old stories and shared new ones. Julian had spent time living in New Guinea, and I had kept his letters, so I shared these with Christian.

Julian died more than ten years ago but to his son, the need to connect with him is as strong as ever. The impact of Julian’s death is something Christian and his siblings will carry for their whole lives.

Once, I might have worried or wanted to move Christian out of this space, again to ‘fix’ things. Now I know better.

Grief over Julian has changed with time.

Jan 21, 2017

Dec 4, 2017

Jan 21, 2018

Jan 21, 2020

Hey Julian, a lot has happened since you left.

Nov 5, 2020