The Covid-19 crisis had its biggest consequences for these two most important rituals, the wedding and the funeral.

“When we were blinded by grief at mum’s funeral, you were our eyes.”

“During the service I never pose people or use flash photography. Discrete candid photography allows me to capture the sombre mode of family embracing, children deep in thought, and friends crofting the bereaved.”

Above photo by The Funeral Photographer John Slaytor, Sydney, Australia

The wedding, with its eyes firmly fixed on the future, is (usually!) youthful exuberance, and its life-giving promise is easier to adapt. Good Grief! watched as weddings did this. But the shuffle to adapt the wedding is not quite so easy with a funeral.

Keri Alexander, celebrant, funeral director and owner of A Better Way Funerals in Sydney, is still seeing the emotional impact of Covid-19 on families.

“It has been a very emotionally confusing time for people – and it still is. The numbers people are allowed to have at funerals keep changing, as we appear to be clear of Covid-19, then discover there are new spikes in the community,” said Keri.

Like funeral businesses everywhere, her business is keeping up to date so it can inform clients: “Our business is in constant contact with the Health Department so we can stay informed about what the numbers are allowed, as our funerals go forward.”

Many people are improvising well, although there are emotional pressures involved. Keri did a funeral recently while the restrictions were capped at 20, although this number has since expanded, in NSW. But this funeral was still complicated by Covid-19, which forced them to run a gauntlet of changes.

“The family had decided to have the funeral celebration at the family home, with their mother’s wicker basket coffin present. Ten people were to be inside the house and then another 10 outside in the garden.

“But under the restrictions, the caterers weren’t allowed to serve 20 people, so the family decided to move the funeral to Sydney’s Macquarie Park Crematorium, which could take 30 people, all at a social distance of 1.5 metres apart.”

Having to remake plans like this is an added stress at an already difficult time.

And at the height of Covid-19 lockdowns, for grieving families we followed, anxiety and feelings of disorientation amplified their sense of loss as they buried people so important to them.

It was a difficult and frightening time. Terrible footage of coffins piled up for mass burials in Italy, New York and Brazil warned what could happen in Australia if we didn’t follow the now enforceable laws about gatherings, at one point with limits on participants down to 10.

Funeral houses risked fines of $100,000 per business and $20,000 per individual if these rules were flouted. Police were also monitoring cemeteries to ensure there were no breaches, something that added to the stress of the time but even now, looking back on it, seems surreal.

These severe restrictions had profound impacts. In one case the mother died at the height of the pandemic, a time when only 10, including the priest and the funeral director, could attend. The family decided that to bury their beloved mother, only in her early 70s, with no mourners in attendance, was unbearable. Her body was held for nearly a month so that 20 could attend. But even then, the numbers felt wrong.

“We had 22 immediate and obvious family members. We made an application to have 22 at the funeral but this was rejected,” explained her grieving widower.

What forever will be etched in his mind was that he had to exclude people. He had to make lists and then cut them. He is haunted by those he told would not be able to attend. And when his family needed to be together to grieve, they couldn’t because of lockdown and this has left its own scars.

Paul’s situation was different but equally as stressful. His 90-year-old father lived in country NSW while he and his family lived in Sydney. His father died on 7 April and he was buried a week later, on 15 April, at the height of the Covid-19 crisis.

“The last twelve months in particular, Dad’s health was very poor. But he was surprisingly happy in his own spirits.”

Paul and his siblings knew that his father wanted his current life, even on limited terms. They accepted that at his stage of life, death was inevitable, but they could not have anticipated the complications to the normal process of saying goodbye.

Paul and his siblings knew their father felt secure staying in, and had reached the point where he didn’t like going out from the nursing home anyway, so they laughingly said he was coping much better with the Covid-19 lockdown than many other people they knew.

“But before Dad died, Covid-19 restrictions affected one of my brother’s more so than me because he lived locally and was visiting easily, whereas I lived in Sydney. Although I came up to visit as often as I could, there would be periods of time between visits because I had to travel long distances to get there,” Paul explained.

Paul’s brother couldn’t visit regularly as he used to do, and this was distressing for him. Like families with elderly parents everywhere, he knew the fragility of the circumstances; were his father to lie dying in his nursing home, family would not be able to gather to farewell and support, particularly at the nuanced yet important time of deathbed unconsciousness.

Another brother, who also lives in Sydney, also couldn’t have visited even if he wanted to because of his own health.

“He has had a chronic neurological disorder for 30 years. His health is such that the risks to him from Covid-19 are very high, so it was imperative that everything be done for him not to catch Covid-19 and he was in strict lockdown in Sydney,” said Paul.

Paul’s father had an episode of aspiration, blocking his airways while in his sleep and he was discovered unconscious one morning. This had happened before and, due to weaknesses that can develop in swallowing in the elderly, can cause death, so the family knew the implications.

The brother who lived locally was able to expand his visiting routine to see their father but only a little, because the circumstances were now end-of-life. But again, there were restrictions. Visits were short. His wife and children could not visit at the same time.

There were NSW restrictions on travel at the time, and Paul had developed a serious eye infection that could have been Covid-19. So Paul had to quarantine. He sat in Sydney, knowing that his father was dying and he was not able to be with him.

“It was a matter of 24 -36 hours from the time Dad was found, until he died.”

By the time it came to the funeral, Paul had received advice that it was legal for him to travel for a funeral. But his travel still had to be delayed. Paul’s eye was getting better and he had received a negative Covid-19 result. But he still needed to be able to keep specialist appointments in Sydney. Doctors consultations were hard to manage at that time and very difficult to reschedule.

These circumstances prevented Paul from being with his siblings to plan the funeral.

So barriers compounded the ordinary sense of grief: to lose a parent is hard, but to know there were extraneous obstacles to connection was very difficult. Yet only a short time later, restrictions were eased. Paul completely accepts the arbitrary nature of the timing, but many others have found this difficult.

“We were spaced apart, following the 1.5 metre social distancing rule. We couldn’t hug anyone, there was none of the physical contact that is so much the thing to do at such times, and I thought was very sad,” said Paul.

The combination of his illness, and restrictions on the size of funerals, meant that Paul’s younger brother couldn’t attend the funeral, so it was live-streamed.

While the family is Catholic and would normally have held their father’s funeral at the local Catholic Church with a full Requiem Mass, there could be no live-streaming from there, since the church didn’t have the technology.

“It would have been great if we could have done this in our own church but it just wasn’t set up for it. Maybe this is something churches can address. If churches could provide that, I think it would be fantastic.”

“Live-streaming was much better than we expected it to be.

“There were other relatives who could take part because of this too, who couldn’t attend because of the restriction on numbers. These were Dad’s older sister and her husband, and cousins and all the grandchildren, including our children who couldn’t be there because of the restrictions.

“The feedback from all of those who watched the funeral live-streamed was extremely positive. They all commented that you almost felt like you were there.”

To ensure the solemnity of the moment, even though they were only watching the live-streaming in Sydney and not physically present, the brother who couldn’t attend and his son, honoured their father and grandfather by dressing formally while they watched, as though they were actually at the funeral.

“The funeral home did a very good job and I’d say to any family if you have the opportunity, particularly a family where a significant number of relatives are either overseas, elderly or live a distance away, definitely do it.

“The actual filming was so subtle that you didn’t realise it was being filmed. We didn’t even know the camera was on and it didn’t affect the atmosphere.”

Three different angles were concurrently filmed, and people viewing the link can switch between these.

“But the saddest and most relevant thing in a way, as a feature of the Covid-19 times, was the inability to have a proper wake after the funeral,” said Paul.

“Dad grew up in that rural area and many people from the community would normally have been there to farewell him. He was also very close to all his nieces and nephews, who’d grown up with him. Only two could be present, within the limit of 10. This created real distress because many of the others would have liked to have been there.

“In normal times that would have been a fantastic opportunity to download, debrief, share memories, laugh your way through your grief with people who knew both my parents extremely well.

“And not to have my own children there was very hard too. Even if we have a similar celebration in six months’ time for Dad, it just won’t have the same raw emotion.”

“Of all the Covid-19 related disappointments, not having family around and in particular his grandchildren there, that was very disappointing.”

Technology and other changes that have come to the funeral because of Covid-19

The expression “forced innovation” is being used in relation to Covid-19. Even if restrictions themselves are lifted, the complications for travel will continue.

“We would live-stream a funeral again, now that we’ve done it the first time. It was also copied to a USB, so that other people can see, who haven’t had a chance to look at it yet,” Paul said.

“Research shows that 35 per cent of families would like to organise a webcast if given the option, but do not know it is possible,” says Australian provider of funeral live-streaming services, Funeralcast.

While these services are gaining traction because of Covid-19, Funeralcast points out on their website that they have been working in the field since 2005.

At the funeral Keri mentioned earlier, the deceased had many, many more friends than were able to attend the funeral, so it was also livestreamed.

“Her granddaughter sang and this was captured beautifully, and others were listening in. We’re very lucky that we have the technology these days to be able to do livestreaming,” Keri said.

There is still room to improve this technology, particularly, the sharpness of the imaging quality.

We also envisage structural changes to the funeral, to accommodate the choreography of the filmed experience, much as has happened to an extent with weddings in more recent years.

Further innovations

- Some American funeral houses have already taken the technology a step further. At one funeral house in Chicago, Dr Sunil Shroff, acting as MC, led an interactive funeral, for his father Chad. With its parallels to a webinar, it allowed people who weren’t present to join in and participate. Messages from those in other places were live-screened as they were written. “This was really interactive, because they could talk to us by typing and then we responded by voice,” Dr Shroff told CBS TV news.

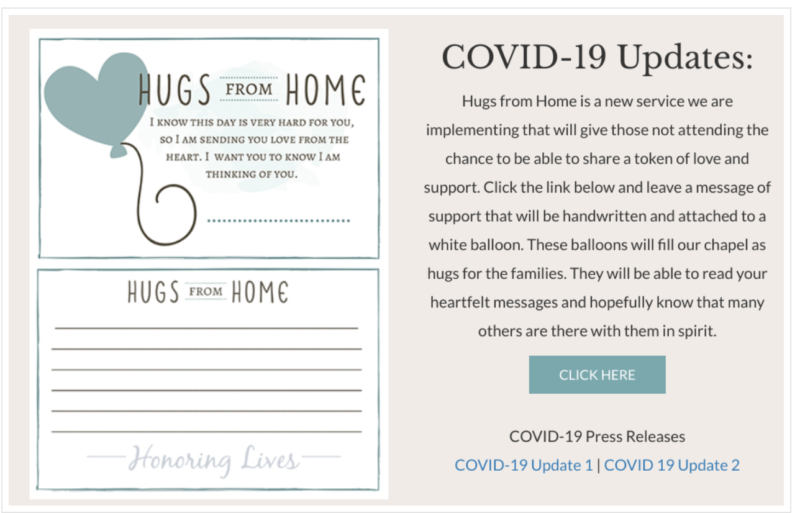

- Recognising the need for people to be able to express condolences without being present, funeral directors are looking at ways to add more depth to the online tribute, for example “Hugs from Home”. In this program, by the US Milner and Orr Funeral Home, condolence messages are tied to balloons which hang in the funeral chapel, reports Rochelle Rietow, from blog.funeralone.com.

- Rochelle also reports that Howard Fields, of The Promise Land Funeral Home in Georgia, USA, has developed the drive through viewing. The body is filmed in the casket and this is projected up on to a screen, in a drive in area. Australians have less of a tradition of open casket viewings, so this might not develop here. However, viewings as an informal, intimate style of gathering before a big funeral are becoming increasingly popular here, so it is possible.

Having mentioned improvements to funerals with technology adopted by some, others will embrace the option for more privacy afforded by the Covid-19 pandemic, relishing the opportunity for smallness.

Good Grief! has spoken to funeral houses who’ve worked with clients who not only accepted the private funeral but were relieved by the limits on numbers, something Keri has seen too: “This follows another trend where people realise they don’t need huge numbers at a wedding but that a smaller ceremony allows a more intimate focus.”

Including a Covid-19 micro one we know of, where the bride and groom stood on the front veranda with only the minister. Her parents, the only guests, were behind the glass doors that led into the living room. There is no record of his parents – the wedding had reached the maximum of five, so if they were there it would have been illegal. But she still got to wear her beautiful dress.