We now have more Covid-19 cases in the community than we could hope to accommodate in hospital. Many will go on to recover without needing the intervention of ICU. But a percentage will need that intervention or they will die.

Who will fall into this risk category? We need to raise awareness in people about what to look out for and what their next step is if their symptoms are starting to frighten them.

NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian has called time on her 11 o’clock Covid-19 news conference, doing her last regular one on Monday, September 13. It’s a powerful symbol of the push to a new normal. It’s time to wrap it up and get on with things. We live with Covid-19 now. With the hoped for 70 per cent and plus vaccination, and no outrageous new variant, it will be with us like the common cold and the seasonal flu.

But as Berejiklian steps down from her news podium, the daily Covid-19 statistics on the NSW Health Department media releases page continue. They are the ones that have over-shadowed her.

Liverpool Hospital paramedics were shocked

The first one, under the heading Novel Coronavirus Statistics, appeared on January 25, 2020. From that day, the stats gradually increased in frequency and now they are a daily offering.

It wasn’t until August 1, 2021, that the first NSW Covid-19 death at home was documented, a man in his 60s, from south-west Sydney.

The reports on his death were unsettling. After he died at home his family drove into Liverpool Hospital to explain to staff there what had happened. Shocked paramedics went to the home but, as the family had explained, he was already dead.

Many people think dying of Covid-19 is like dying of the flu, ‘the old man’s friend’ so called because the patient develops a fever, slips into unconsciousness and dies. But the preamble to a Covid-19 death is usually dramatically different to that, the reason graphic interviews and images of people in Covid-19 wards, struggling to breathe and painfully aware of it, are being released to the media.

At that August 1 news conference, Health Minister Brad Hazzard urged people to seek medical help before it’s too late. And he pleaded with new Australians who may fear or distrust authority to seek help if needed: “Our government, the NSW government, is perhaps not like the government that you have lived under overseas. We are here to support you.”

“Very sadly, we are seeing more families coming in with a family member who is presenting not alive, but dead,” Hazzard said.

So the 60-year-old man from Liverpool wasn’t the first, even though he was the first documented in the statistics as a death at home.

In fact, there had been at least two others. One of these, two weeks before, was Saeeda Akoobi Joujo Shuka, 57, and her death was very public.

She was the mother of two removalists charged with breaching public health orders for taking their van across western NSW while one was Covid-19 positive.

Language barriers create issues

They later defended themselves by saying their English was too poor to understand the health orders they were given.

“The language barrier was an issue, they have only recently arrived in the country and cannot speak English very well, which meant they couldn’t understand what was going on,” their community leader, Samir Yousif, president of the Chaldean League, explained.

Their community pointed out that as their mother lay dying, the family were copping abuse for the breach. NSW Health said she was offered care in hospital but refused. Media reports suggested the mother was too afraid of a punitive response if she went to hospital, the reason she refused to go.

When discussing Shuka’s death several weeks later, at the August 26 Covid-19 news conference, Hazzard again said authorities were particularly concerned about families where English is a second language, especially refugees.

“What we’re seeing in particular is refugee family groups, and often large families, and often there might only be one or two people in the family who are income earners, we’re seeing a reluctance for them to come to health authorities and say, ‘we have a problem in our household’,” he said.

Representatives of multicultural communities said then there was an urgent need to improve health literacy in these vulnerable communities.

16 more deaths at home were to follow

But since then there have been at least 16 more deaths of people at home and some of them have not even been tested.

They include:

- Aude Alaskar, 27, of Warwick Farm, who died at home

- a 40-year-old unnamed woman, who died at home alone in Cabramatta

- Ianeta Isaako, 30, of Emerton, who died at home with her husband, Sako, and three small children present. Her husband was later hospitalised for Covid-19.

- William Orule, in his 30s, recent immigrant from South Sudan, who also died at home alone in Western Sydney.

Good Grief! is very committed to increasing the opportunities for people to die at home under good and humane palliative care systems. But this works for people dying of chronic illnesses – rather than acute illnesses such as Covid-19, and it requires a reasonable understanding by the patient of the implications of medical decisions made.

At the August 26 Covid-19 news conference, Dr Lucy Morgan explained dizziness and breathlessness was an indication a person required urgent critical assistance.

“Don’t ring up and make a GP appointment (if you’re experiencing breathlessness), call an ambulance because these other sorts of symptoms and signs tell me that the Covid-19 illness is progressing and progressing quickly,” she said.

“As people become increasingly breathless, the oxygen in their blood starts to drop and they need increasing levels of extra support to keep those oxygen levels up.”

From then on, they need ventilators, she explained.

By the time Orule’s death was reported at the September 3 Covid-19 news conference, NSW Health was bringing more experts in to stress the need for people experiencing breathlessness to call an ambulance immediately.

NSW Health confirmed in the Daily Telegraph on Friday, September 10, that at that time there were more than 11,000 people with Covid-19 in NSW. Of these, 1156 cases were being managed in hospital, 207 in intensive care and 89 of them requiring ventilation, many for the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) associated with Covid-19.

A global literature survey completed last year by a team from the Medical University of Vienna, suggests that 20 per cent of Covid-19 patients will be ill enough to require hospitalisation.

Should 2200 be in hospital, not 1156?

Using that calculation, Of the 11,000 at home in NSW now, 80 per cent, or 8800 people, fortunately, will not become terribly ill. They will have headache, fever, muscle aches and lethargy that is manageable.

But also using that calculation, 2200 would be in hospital now, nearly double the number (1156) who are actually there at the moment.

Vienna is a long way from Sydney and the study pulled together the literature from seventeen studies reporting results from 2486 hospitalized Covid-19 patients in five countries. The medical culture in those countries might be quite different to the Australian one. So let’s look at NSW figures from the first wave of the pandemic, The Covid-19 Hospitalisations in NSW, for the reporting period 1 January to 19 April, 2020.

These figures show that of 2988 Covid-19 cases during that time, 372 people were admitted to hospital, that’s 12.4 per cent of those with Covid-19. If the ratio of admissions were the same this time, that would be 1364 people, a little over 200 more.

We hope the lower admission rates now are because more people are vaccinated, so less ill. We also know that medical treatments have also improved. But are people receiving the care that they need?

Because the NSW hospital system is currently overloaded, home based treatment and management is being utilised more. But with 18 Covid-19 deaths at home without any medical support, is that system coping and adapting to the new circumstances?

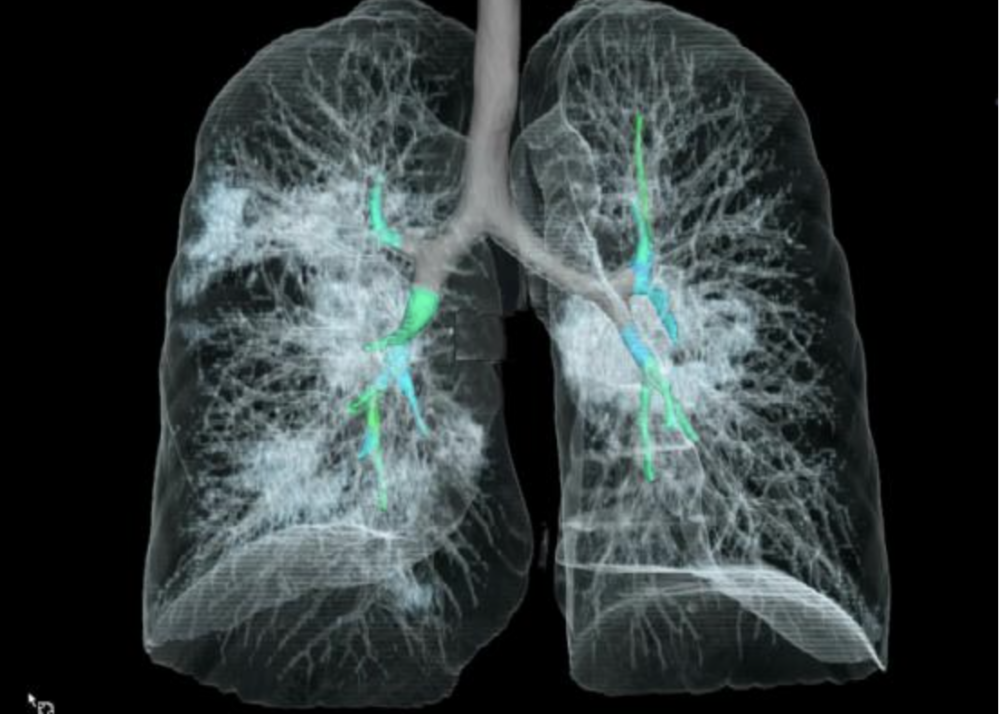

Again, looking at the Viennese study, it says that of those transferred to an ICU ward, 75 per cent will be there because they developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

We can’t predict who will develop ARDS

We still can’t predict who will develop ARDS, once they develop Covid-19 pneumonia and how suddenly they will deteriorate, which presents a triaging challenge. To add to the confusion, even though it is recognised as a sign of serious illness with Covid-19, shortness of breath can be experienced as an early symptom even with normal vital signs.

The dilemma is that most people don’t really know the significance of their Covid-19 symptoms, or how to read them. People often present at Accident and Emergency with the headaches and fevers of the early days of the disease, only to be told to go home.

And paradoxically, just as we have health authorities urging people to come forward with symptoms, we are also being told in the media every day that the system is overwhelmed.

Indeed, the sticker on the back of the ambulance says ‘save triple zero (000) for saving lives’.

We need basic information in plain English

Others don’t want to go to hospital because they won’t be able to be with their family. Some have been put off hospitals because of the number of people who’ve got infected with Covid-19 in hospitals, even though they themselves have already got it.

Then there is the problem that some people who are hypoxic, that is have low oxygen levels, don’t realise how sick they are.

Problems managing the needs of all these people go well beyond language barriers. The issue is another type of literacy problem – this one’s about health literacy. The lack of understanding covers a much wider net of people than those who struggle with English.

And this goes back to the problem of reporting over the phone.

Those with minor symptoms are largely being managed with telephone services, which rely on patients’ reporting their symptoms and relaying information about their oxygen saturation levels (often just referred to as ‘sats’). This is done by applying a pulse oximeter to the finger which uses infra-red to measure oxygen levels.

Does everyone who’s been told to use one understand the importance of this?

NSW Health told The Daily Telegraph on Friday: “Every Local Health District has dedicated Covid-19 community care teams to provide virtual care and daily clinical and welfare checks for Covid-19 patients at home.

“The daily clinical checks assess patient condition, and there are clear escalation triggers in place for medical reviews and transfer to hospital if needed.”

But the son of one man who died at home, who doesn’t want to be named, says this escalation system didn’t work for his father.

“I don’t believe my father got the attention he needed. If he had, he’d still be alive today,” he said.

“I thought nurses or doctors would be coming every day to check on him but they only came every three days.”

Instead, his father was contacted by telephone every day. His father didn’t leave the house for medical attention once his Covid-19 was diagnosed. He never saw a doctor. No medical professional supervised the monitoring of the ‘sat’ levels, effectively, he said.

His father was told to measure his oxygen saturation levels using a pulse oximeter. The one he was delivered – without seeing a person – was broken, so his son went to the chemist shop to buy him a new one.

But his father had an underlying heart condition. When his breathlessness reached a critical point he got into the shower. He died there of a cardiac arrest.

“All the attention was on other family members because of their histories of problems such as asthma. Meanwhile, my father was slowly going downhill because of his heart and no-one realised it. He didn’t complain of anything,” his son said.

In NSW, the peak of the covid-19 crisis is expected in October.

If you are at home and symptoms develop rapidly

Ringing an ambulance is a good next step. Sixty new paramedic interns started with Ambulance NSW on Saturday, September 11 and another 130 will be joining by September 27.

People need to be educated about what the ambulance service can provide forthem.

Few people realise that if they’re transported to hospital with Covid-19, this doesn’t cost them anything.

Importantly, those who enter the hospital system via ambulance will enter under a Covid-19 protocol that is safe for everyone. There are plenty of stories of Accident and Emergency staff having to cope with the challenge, when ill patients with Covid-19, who’ve been at home, walk into the Emergency Department, putting other patients and all the staff at a high risk of becoming infected.

Over the last two weeks, Ambulance NSW has developed its system for integrating data on hospital bed availability, with the ambulances on the road. So it is hoped this will help minimise ‘ramping’ where an ambulance arrives but waits hours for the patient to be admitted.

We also look forward to seeing interpreters for those with English as a second language, being brought more effectively into tele-health and improved tools to help people with poor levels of health literacy, whatever their language skills.

Most of the 18 deaths at home to date have been referred to the NSW Coroner. So with luck a forensic review will happen allowing scrutiny and recommendations that will ensure long term improvements to the management of Covid-19, when this is being done at home, an inevitable scenario for the future.

Here is what you need to know:

- If you get a positive Covid-19 result, you will be told to isolate at home, no matter how fit you feel. NSW Health officers will contact you to talk about your health. You will receive regular police checks to ensure you are isolating.

- Your GP will be contacted too, if you have named them on your Covid-19 testing forms. If you are not ill enough to be transferred to hospital, which is about 80 per cent of cases, you can still expect to be monitored by health professionals, usually by telephone. If you don’t feel you are getting enough information, you can ring your GP, or ring your local major teaching hospital and ask for ‘the duty public health officer’. They can either discuss your case and your management or give you information about who you should speak to next.

- Is English your second language? If so, you are able to request an interpreter. This can be done through the Australian Government’s website but the hospital looking after you will help you with this too. Remember, if you are to be hospitalised, your family members can’t be present to help interpret for you.

- Are you avoiding contact with the medical profession because your household composition makes it difficult to isolate? Discuss this with the contact tracers and NSW Health when they ring. They have services at hand to help deal with this situation.

- About 17 per cent of people with covid-19 have no symptoms at all, according to an Australian study. This is in contrast to other research which suggests the figure is 42 per cent. The background debate about this is discussed in the RACGP’s NewsGP. If the subtle differences between individuals is not clear to scientists, don’t feel embarrassed about asking your GP or other doctors for further explanations and reassurance.

- If you are one of the 80 per cent who only has a mild illness, this is likely to include coughing, fever and shortness of breath. Shortness of breath at this stage can be tricky. Is it associated with the shortness of breath that comes from the more serious developments that occur in some people – maybe pneumonia and ARDS, or is it harmless? Sometimes, although rarely, you can feel quite normal, even though you are not getting enough oxygen.

- To help distinguish this, you can use a pulse oximeter which you place on the end of your finger. Usually, this will have been delivered by NSW Health even if by post. If you haven’t been given one, they can be purchased at a chemist shop.

- The chills, aches and pains and other symptoms of the early stages of Covid-19 can develop into pneumonia in about 15 per cent of people. This is an infection in the lungs and is a complication of respiratory illnesses. Symptoms of pneumonia can include muscle and body aches, shortness of breath, dizziness and heavy sweating. The sufferer is usually much sicker than they were with the similar but not so serious symptoms earlier in the course of the disease. If you think you might have developed these symptoms ring the ambulance on 000 immediately. The development of pneumonia means that you are likely to need oxygen. Sometimes this is delivered with nasal prongs or an oxygen mask, depending on the level of hypoxia. For a range of reasons, oxygen delivery is done differently for Covid-19 patients. You are too sick at this point to manage this yourself. Trained hospital staff can and they have the equipment to make records of your condition for continuous monitoring.

- Other illnesses, such as heart disease, and diabetes will be impacted by your Covid-19 illness. Being obese will also increase your risk of becoming sicker. So with all of these conditions have a low threshold for deciding when to contact the ambulance. If communication is difficult, tell them the names of the medications you were on before you got sick with Covid-19.

- About five per cent of those who develop Covid-19 related pneumonia or need to be hospitalised for shortness of breath will develop more serious conditions, such as Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

In NSW, if your symptoms get to the point where you are frightened they are life threatening don’t ring a GP or your local hospital. Ring 000. Ambulance NSW paramedics are trained and equipped to transport you to hospital if this is needed – or to treat you at home if you are well enough, and then to ensure you get access to the health services you need.

To reach NSW Ambulance – ring Triple zero (000)

Further discussion at https://good-grief.com.au/a-tale-of-two-cities/

and

The ABC’s discussion after Q&A on Thursday night.