Work has gone online – even, surprisingly, in the healthcare space. We’ve discovered more about what’s effective and what isn’t as lawyers, school teachers and sales people have developed new online practices.

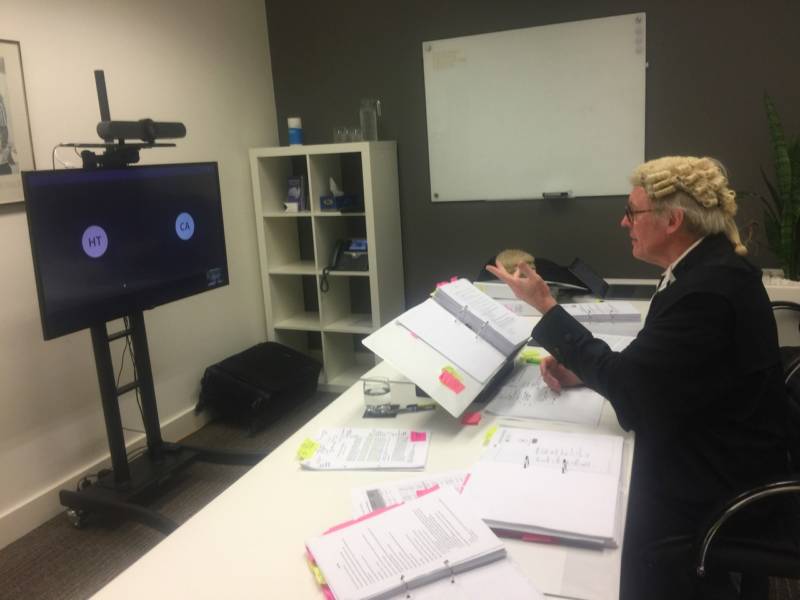

However, at times this can feel like two steps forward, one step back. Some Sydney lawyers report that big, central NSW government servers servicing courts became overloaded, causing problems, which in turn threaten the delivery of justice.

This was amplified when NSW public servants, including its lawyers, were warned not to use Zoom in the early days of Covid-19 work from home because of the platform’s security issues.

But such platforms will improve and respond, and their take up will continue.

“Zoom usage has soared from 10 million daily meeting participants back in December to 300 million in April. Microsoft recently recorded 200 million meeting participants in a single day. Google Meet is adding roughly three million new users per day. If nothing else, COVID-19 has taught us people can work from home,” says the ABC’s James Purtill.

And this new capacity extended to telemedicine, even in areas we might never have thought possible before, such as those cardiology consultations previously unthinkable outside a surgery. Many consultations conducted over the phone are reported to have gone well and this could result in permanent change.

The pressure on diagnostic services such as medical imaging and breast screening to continue to deliver their services, working laterally with social distancing and new approaches to gathering people for appointments will set an example for other areas of medicine.

IT’s role in other aspects of health care delivery, again going back to the example of cardiology, will expand into areas such as rehabilitation.

A study led by Sydney University, published in 2017, looked at 282 cardiac rehabilitation patients, inviting them to use a closed Facebook group to keep in touch with professionals and exchange information. Unsurprisingly, it showed that the more familiar patients were with using Facebook generally, the more inclined they would be to use it for this purpose.

Such closed groups will no doubt develop as a tool in other areas of medicine, now that Covid-19 has changed work practices.

For more, see:

Partridge SR, Grunseit AC, Gallagher P, et al. Cardiac Patients’ Experiences and Perceptions of Social Media: Mixed-Methods Study. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(9):e323. Published 2017 Sep 15. doi:10.2196/jmir.8081

Covid-19 takes end-of-life management online too

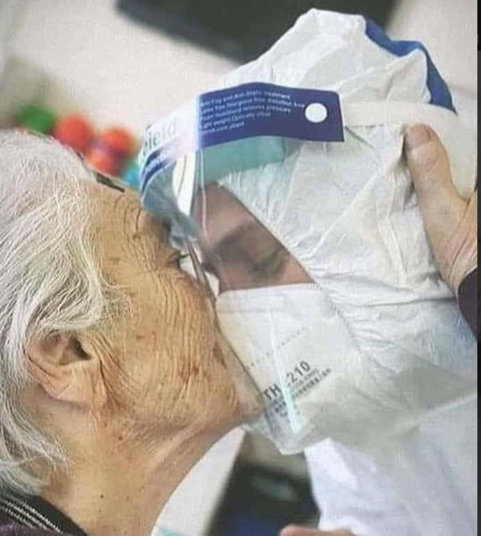

Mary Bardin, Operations Manager of the Alzheimer Society of Ireland, shared the following post on her LinkedIn page. It relates to a 98-year-old woman in a nursing home. For such an incapacitated person, the end of life is close.

“She’s 98, and the isolation and loneliness came over her in a river of tears at my visit. Not able to see her son or daughter for 6 weeks. She wants to die. Because at 98 the waiting is too much. I offered to FaceTime her son. She cried more. She wanted a real hug. I in my PPE said enough. I too bent over into her arms she wrapped so tight around me. I broke the rule. I hugged her till she could breathe. We both had a healing. I’d do it again. Love matters most.

“The older folks in long term care haven’t been touched or hugged. It’s causing failure to thrive. Hugs are a necessary part of living.”

And dying too.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that a number of Australian palliative care institutions were able to find ways to ensure connection in end-of-life scenarios. In one case we know of, a complete family were allowed at the bedside as long as they adhered to strict quarantining protocols after the death and in another, hospital technicians provided very high quality face-timing for an elderly dying man, so that all three children maintained their strong connection to him.

But there are still gaps and inconsistencies, both in Australia and overseas. In Canada, the ‘Saying Goodbye’ campaign was launched by the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association.

“While certain provinces have taken steps to relax visitation protocols for end-of-life situations, many hospitals and long-term care homes still do not allow family access, even with personal protective equipment (PPE).

“Every Canadian deserves the chance to say goodbye to their loved ones, even in an unprecedented crisis such as COVID-19. There have been too many heartbreaking stories of families who were unable to say goodbye due to extreme restrictions on end-of-life visitations. While health and safety must continue to be paramount as we fight COVID-19, we can do better as a society by promoting a more compassionate, inclusive visitation protocol that embraces hospice palliative care principles and dying with dignity.”