This is a review of where we are now, the gains and losses in managing the threat of death from Covid-19. What has changed, what has gone backwards, what has improved? Not all the threats to life will come from the virus itself, a space that health professionals are now focusing on.

New Covid-19 cases are starting to spike in most western countries, and with the gradual fall down the other side of the infection rate comes hope for a return to normal. The sense of threat from Covid-19 is rearranging itself, changing from a sense of imminent crisis to something with softer but broader implications.

Technically, the economic slump is also bottoming out – although the effects will continue to ricochet. Fitch Ratings of London in its May 26 report said the slump in global economic activity is close to reaching its trough, while McKinsey’s May 27 Briefing on Covid-19 Implications for Business, says many parts of the world are starting to reopen, with consumers in Europe, America and Australia keen to get out and shop.

But Covid-19’s run is far from over. Its worldwide deathrate still grows, moving towards the 400,000 mark in a fraction of the time it took to reach 300,000.

Impacts on world trade – and what this means for health

Felix Richter of the World Economic Forum pointed out on 29 May:

“The World Trade Organization has predicted that world merchandise trade could plummet between 13 and 32% this year, because of COVID-19.”

With this shrinkage comes the threat of recession, world-wide.

“Growth is likely to be flat to negative in seven of the ten largest economies in the first quarter. These include: China, Japan, Germany, the UK, France, Italy and Canada. Brazil is now at more risk as it depends heavily on exports to China and is now dealing with its own exposure to the virus. Global growth is expected to slow to 1.8% in 2020, well below the 2% threshold that indicates a global recession,” said US economist Diane Swonk in a 4 March report, An Economic Pandemic: COVID-19 Recession 2020, that still holds.

‘Insular will replace global’. Disruption to the supply chains of goods will continue, changing international trade and having adverse effects on globalisation for years to come, although many would argue that modification was overdue.

But as Diane points out, this means the manufactured parts that were shipped from one port to another won’t be sent now. Dockworkers will be laid off (longshoremen in the USA). This will cause delays in finalising production. This, in turn, means job losses and the health consequences of that. It also means impacts on healthcare supplies – PPE, pathology testing, vital pharmaceuticals where attention will focus in the next 18 months.

The majority world

The implications of both the virus itself and supply of food and products to poorer countries will be savage.

“Provisional projections from the World Health Organisation (WHO) suggest more than 10 million people could be infected by Covid-19 in the next three to six months,” reported Al Jazeera on April 17.

This includes steadily increasing numbers in Africa, where WHO warns deaths will be higher than those in Europe and America. There are also overcrowded refugee camps throughout the world, particularly the Middle East and Turkey, where social distancing is not possible.

At the same time, the deathrate in India is currently low, likely grossly underreported. But it is rising and the next three months will be revealing for India’s Covid-19 story.

Because of Covid-19, delays in regular immunisations against polio, measles, cholera, yellow fever and meningitis, will affect about 13 million people, worldwide, as WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has warned.

WHO has also warned that COVID-19 amplifies risk of worldwide food-price spikes and severe disruptions to food supplies. These will be critical in those places that are already vulnerable to risks in food supply.

For more, visit here.

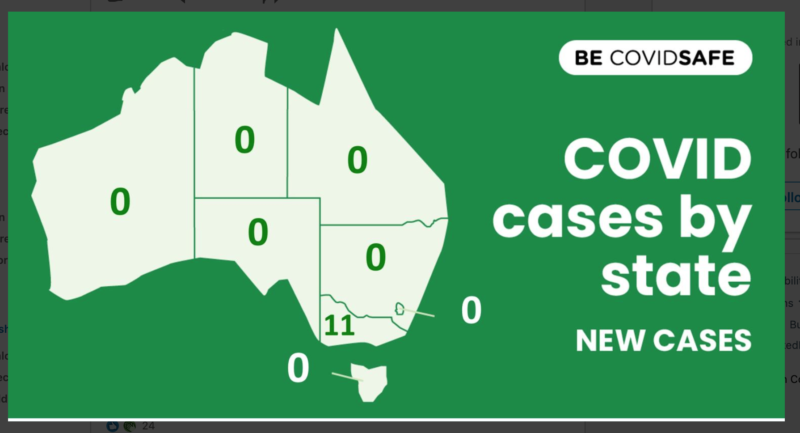

Health impacts in Australia

In Australia, the Jobkeeper and Jobseeker schemes have been put in place to damp down estimates of more than one million Australians losing their jobs. But even with these in place, the Australian economy is expected to be impacted by Covid-19 until at least March 2022.

Nathan Grills in Covid-19 Containment, poverty and population health in the Medical Journal of Australia’s Insight explores in detail the implications.

“It is probable that the poorer will differentially bear the greatest burden from the economic cost of containment,” he says.

The Age’s Melissa Cunningham reported on 13 April that Australia’s pathology sector had recorded a 40 percent drop in routine testing, which meant diagnoses of cancer patients were delayed, with the inevitable consequence of later diagnoses of more advanced cancers.

The Australasian College of Emergency Medicine has made similar warnings: “By delaying seeking medical attention for severe illness or health issues such as heart attacks, asthma or abdominal conditions such as appendicitis, patients risk making their situations much worse. In extreme cases this can be life threatening, something we have learnt from other countries such as the UK.”

“Not seeking treatment can cause mild to moderate health issues to worsen over time, which risks placing a greater future burden on our healthcare system at a time when it is unclear precisely when the COVID-19 situation will peak.”

Ian Hickie of the Brain and Mind Centre has predicted a 25-50% increase in Australian suicides over the next five years, as a consequence of Covid-19.

For Greg Jericho’s prediction of Covid-19 impacts until March 2022, visit here.

Indigenous Australians

Australia’s Indigenous people are more vulnerable to Covid-19 because of underlying health problems, The Australian Medical Association points out.

“The burden of disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is 2.3 times higher, potentially preventable admissions to hospitals are 32 times higher, and potentially preventable deaths are 3.3 times higher than that of the non-Indigenous population. 64 per cent of the burden of disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is due to chronic diseases,” The Australian Medical Association says.

This means the risk of death from Covid-19 is higher, amplified by the fact that: “In 2018, chronic lower respiratory disease was the third highest cause of death overall for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in NSW, Qld, WA, SA, and the NT.”

For more, visit here.

Health impacts in the USA

In the USA it’s no surprise to find that fault lines, triggered by Covid-19, are now more exposed.

US racial tensions have been inflamed by the outrageous death of George Floyd, yet another black American to die at the hands of a white policeman.

The impacts of the cross-over between racism and Covid-19 for black Americans is poignantly explored in Vox by A. Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez in The Unbearable Grief of Black Mothers.

She makes many points but the two stand outs are: “When unmasked, we Black mothers fear our loved ones will suffer from the risks associated with complications from the disease. When masked, we fear the risks associated with complications of bias and racism.”

And: “Black Americans between ages 35 and 64 are 50 percent more likely to have high blood pressure, three times more likely to have kidney failure, and 60 percent more likely to have diabetes than their white peers. These are all conditions that leave us more vulnerable to Covid-19, too.”

The scenes that run in the open credits of the futuristic political espionage series Homeland could be Minneapolis this week. Does Covid-19 feed racial tensions, which in turn reveals political flaws? US media reports indicate yes, although some commentators say it is more complex than this.