This article was updated on 31 August, 2022. It features a funeral photographer capturing kindness.

As Good Grief! roams, peeping in quiet corners, delving into resources from country to country and looking at new and old ways of doing death, this one has popped up, right on our doorstep, only a suburb away.

John Slaytor is a funeral photographer capturing kindness. Yes, that’s right. While he’s also an award winning portrait photographer, one of his favourite ways of exploring the art of photography is through funerals.

In recent years he’s combined this with the creation of funeral books and both are now an important part of his funeral photography business.

“I began this journey when a friend who had seen a book of my Indian photography asked me to take photographs at the funeral of his favourite aunt’s husband’s funeral.”

Expectations were upended

It wasn’t what John thought it would be: “I was expecting the widow to be a sobbing wreck, but she wasn’t. She was the one supporting and sympathising with others. She was a source of energy, the one who was holding everyone.”

“And I realised then that I knew so little about funerals and that’s what really sparked my interest.”

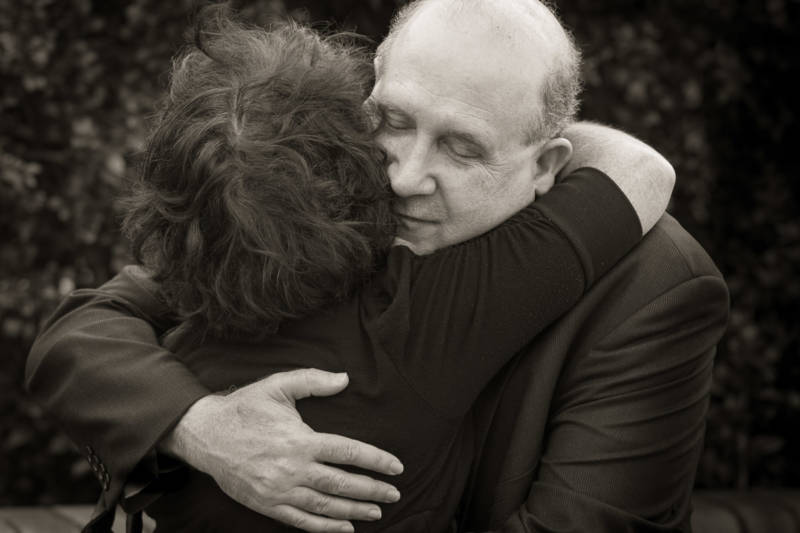

John’s funeral photos are all un-posed, the great secret of their success. There is nothing theatrical or contrived about them but they create extraordinary scenes of tenderness. And as he says: “My images are not about sobbing people. Very rarely are people crying.”

“Ultimately what motivates me is to capture people being kind to each other. It’s really simple, it’s just people loving each other and this is something you see at funerals. And I just think we need more evidence of that,” he explained.

Mourners don’t notice him and that’s exactly as he wants it to be because when they look back – whether it’s days, months or years later, they will see in his photographs how they felt that day, not what they thought they should look like or a glamorised and artificial persona they wanted to project.

John is hidden in the funeral crowd by his desire to be anonymous, and this enables him to deliver truth and sincere emotion to his clients: “I leave my ego at the door.”

Does the same thing happen at a wedding?

“These days, not really. So often, the way weddings are structured now, couples are stepping into the pages of wedding magazines and copying what they see there and that’s not real. So in wedding photography, so much is so fake.”

Keepsake books – The Funeral Photographer

“As I explored funeral photography, I came to appreciate that funeral books can take on the role of practical grief therapy. Some families clearly benefit from the process of creating the book,” he explained.

John is careful to point out that the funeral book – both the piece of property and the spirit of it do not belong to him. He crafts this permanent memorial, an intense experience, but then he hands it on.

It’s not my book at all

“It’s not my book at all – it’s really the book of my client and all I’m really doing is facilitating that customised memorial. So I say to them, they can have whatever they like in the book. I help by making suggestions about the content. These can include the tributes, the eulogies, maybe photos from their lives and or their favourite poems.”

“I even had one client whose wife had died and received her degree posthumously. So we included not only an image of her degree but also of her daughter accepting it from the University Vice-Chancellor on her behalf.”

“The same family took the ashes back to their ancestral village in Kenya and the book included photos from that trip as well. So this shows how personalised the books can become.”

“One widow asked me what she could put in the book and I explained that it was her book, that she could put in anything that she wanted.”

“Initially she gave me two letters written by her young children to their father on the night of his death, which I scanned and they became part of the book. After two sessions spent shaping the book, seeing how deeply she was grieving, I suggested she might like to write her own letter to her husband for inclusion in the book. She loved this idea and her letter was added and that became a very important part of the book.”

“It was as though she needed me to grant her permission to do something that she was quite capable of permitting herself to do.”

“When I gave her the book at the end, she didn’t want to look at it in my presence and I realised that was because it was now hers. It had become hers alone.”

“And I really liked the idea of that transfer. It was not my book anymore, it was hers and that felt right. In a sense it’s like I am a builder, who constructs your home and crafts all the finishing touches to it – and then I hand over the keys to you. It’s that same idea. It’s the same reason that I don’t put my logo on the book.”

“So my books are an attempt to create a permanent memorial to the dead, like we always had in the past, but in a modern way. It’s quite an ambitious goal, but we live in such a visual age that it makes sense to deal with death via images.”

“Our culture once allowed us to memorialise the dead. In the olden days, the tangible, permanent memorial was the gravestone. Then this shifted to ashes on the mantelpiece and then we had nothing. Now we have funeral books,” John explained.

John let me hold and slowly explore two of his funeral books. One was of an Aboriginal elder’s funeral in Sydney’s Redfern. The photography is intense. Close in, John has captured the sense of community in the group.

They are not photos of people standing alone, but people in large groups, spilling out of the photo, signalling the gathering of the clan to support the bereaved, that goes to the heart not just of mourning but of honouring the dead and who they are as a kinship group.

“To that community, expressing their connection to family networks at the funeral just by being there was so important. It was as important as focusing on the deceased. I realised that to this community, relationship with others in the group was a key part of their lives and therefore their funeral ritual.”

Another book honours a stillborn baby. Her rosebud lips are settled in contentment. Her closed eyes look for all the world as if she has just pulled herself off her mother’s breast and fallen into a deep, satisfied sleep.

It is the wicker basket, carried in ceremony so easily in her father’s folded arms that gives the clue that something is amiss. And then as you go through pages of the book, as the story of the funeral unfolds, there are photos of pained people validating this little life, even though she never drew breath. There are grandparents, eyes swollen with tears. There are best friends of the parents standing at the lectern, reading poems they’d written about unfulfilled love, that will later appear in the book.

“The book was a wonderful way for her parents to honour their daughter. They could do this by spending time putting together the book and making sure it was perfect, rather than pretending that her birth hadn’t happened and sweeping everything about their baby daughter under the carpet.”

“But as well, the book allows them to revisit the funeral long after it had passed and it gave them something to do, as they selected photos, helped arrange pages, fine-tuned and tweaked the book.”

The philosophy behind John’s photography is about allowing death to intrude, to make its way in to us, to sweep a path into life.

“I don’t think our culture’s denial of death is healthy. And I think we need to somehow restore death to give meaning to our lives,” he said.

To see John’s website go to: thefuneralphotographer.com.au

To contact John, go to: info@thefuneralphotographer.com.au

For information about A Good Death, a compassionate and practical guide to prepare for the end of life, go to: https://good-grief.com.au/a-good-death-book-margaret-rice/