This newsletter formed the basis of my talk with the Lifting the Lid online International Festival, in November, 2022.

Well, not so easy really.

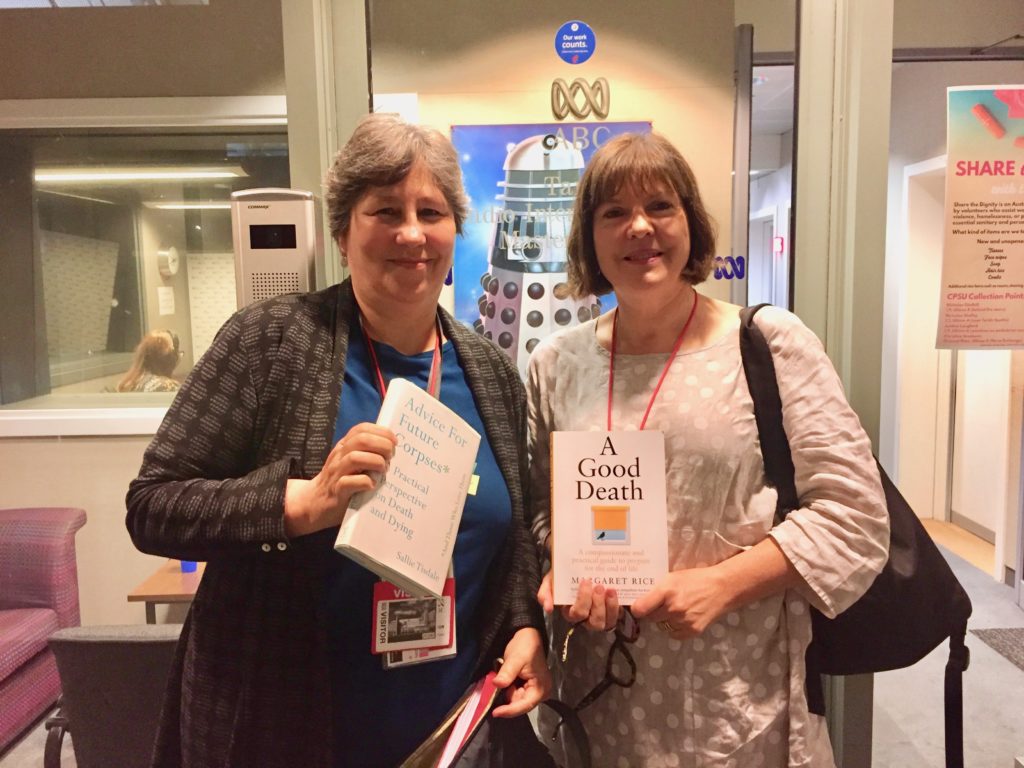

Of course, to paraphrase my friend and fellow death writer Sally Tisdale I have never died so what would I know?

I’m also relatively young, at 63, so I have not been on the fuller journey of loss that the 80- year-olds I know have been on.

But I’m going to humbly put forward this list, based on more than 10 years of close observations of death in our society.

Despite wonderful social developments, most of us still don’t quite get the early planning right.

It’s like we pack our bags extremely well. Some have fine things in a Louis Vuitton valise, and they’re travelling first class. Others pack a strong cardboard box, equally as effectively and just as securely.

But the trouble is, they’ve got their bag packed but the only thing they know about their destination is that they hope it’s a good one. They don’t know where it is. They haven’t thought about how they’ll get there and haven’t decided who they’re going with.

To illustrate, one man I sat with when he was dying, gave a lot of attention to getting his will in order. But in doing this, he fell into an obsessive hate for his brother, which impacted on the way he felt and how he dealt with the nursing staff in his palliative care ward. As I sat with him, I found myself wishing, for his sake, that he had focused on more than just his will. This sort of missed opportunity for psychological healing is common in all of us at all stages of life but can have a very big impact when we are dying.

My list of five things all involve small recalibrations when we are young, fit and well. But they become harder to manage the longer in life we leave them.

Step one: Address your end of life wishes.

There’s been a lot of social and policy progress in the time since I’ve been writing on the subject, addressing end of life wishes and preparing the paperwork that goes with it.

Where do you want to die? Who do you want around you? Are you hoping to die pain free? Do you want to die ‘off-grid’, in your own home, away from hospital care?

Do some basic research about these questions. Good Grief! resources can help you with this.

Recently, a woman told me she wanted to die pain free, supported by all the drugs available to make this possible – but she hated doctors and refused to have a general practitioner or any other doctor in her life.

So achieving her goal was going to be very hard. In Australia, a relationship with a good GP opens up avenues to good palliative care, either in a hospital or in the community. If you engage with the medical system – even if consciously taking a ‘no-hospital’ approach, you will be able to access the pain relief, and other supports you are entitled to at death. This is typical of the practical considerations you need to make. And pain could be a big part of your death although not necessarily.

Pain needs to be mentioned early. While most people dying won’t experience much pain, for those who do, this will be their major challenge. A struggle with pain, whether at death or any other time in life exhausts, preoccupies and dominates. The following four steps will seem irrelevant if this is not addressed. Once pain is under control, the dying person can refocus. But background psychological issues, for example, fear of death, anger over dying and conflicts with family will amplify pain and suffering. So if you have resolved these then it can be predicted, from observations and evidence, that you will have a more peaceful death.

You might decide to go with alternatives to the medical model. This can be done and there are people who can help you with, for example, interventions such as mindfulness and meditation. But this is a whole of life approach and if you want to take this path, you need to plan for it and in some cases make a big shift in consciousness.

A lot of change is happening in approaches to the end of life. Today, professionals want you to be more involved and to state what your wishes are. For example, do you want to die at home? Do you want to be resuscitated if you have a major heart attack but other severely life-stye limiting conditions such as dementia? Do you want to have medical intervention at all?

But the current reality is that, over and over again, reports and statistics show that people know what they want but don’t communicate this. This was brought home to me this year, 2022.

Staff at a hospital I’m involved with estimated that only five per cent of their patients had their end of life wishes documented. Yet it’s a typical large tertiary hospital and statistics show that more than 53 per cent of those in such a bed are over the age of 65.

So think optimistically but plan pessimistically. Write down how you would like to be managed, in a way that is both legally binding in your country, state and region and acceptable to the medical professionals who will work with you.

Technological developments will make this a lot easier, over the next ten years.

Step Two: Learn how to talk to doctors.

You cannot predict the medical events that could lead to your death, when you’re fit and well. There are so many different scenarios. But there are many diseases which follow a very predictable path from first diagnosis to death.

To help come to terms with the diagnosis of a new disease find out what the statistics are around survival patterns with your disease, as people with it age. Also ask your medical professionals for a frank discussion about possible scenarios, asking “Can we talk about the possibility I will die?”

If you are having surgery, learn now how to ask the right medical questions early, including, what is the risk of death from this procedure?

If you can ask this question while you’re young, you’ll be better at asking it when you’re older and then well prepared to approach your surgeon and other doctors as an empowered individual, when you are elderly and physically vulnerable going into surgery.

It also means you will be able to rely on yourself, rather than being dependent on younger relatives, when decisions about your health care are being made when you are elderly.

Step Three: Address the question ‘how afraid of dying am I?’

Death fear is not to be underestimated, although for many of us it is hidden in plain sight. The more afraid you are, the more likely you are to push the practical planning away.

But there is a much more fundamental impact on you. The greater the fear of death, the greater the fear of life, they are that interlinked – although we often don’t realise it.

And additionally, the more fear we live with, the more anxiously and miserably we live. So ask yourself “What is my fear of death doing to me?”

Unfortunately, in our culture today, very few elderly people are encouraged and given the skills to have this conversation. We don’t provide the educational and psychological supports needed for this age group, about this question. It will be an exciting age we live in, when this addressed more effectively.

But in the meantime, assume you will have to address this yourself.

The great religions of the world have well developed ways to help people manage this question. ‘How afraid of dying am I?’ becomes a question of whether they see their death as leading to God.

But this simple premise can cause a lot of misunderstandings. Some people rigidly stick to their faith because they believe it will help them cope, but still die very frightened. Do people with faith die happier? Not always. And I have spoken with families and palliative care staff watching someone with no belief in an afterlife, who has died very calmly, peacefully and unafraid, in one case a profoundly spiritual death that brought his carers to their knees.

The philosopher Eckhart Tolle says all the great religions help people find spiritual peace because they teach people how to detach from their egos and their mind and enter simply, the state of ‘being’ not thinking.

This not only helps with everyday life but is a good part of our repertoire to take with us through life and towards its end.

Mindfulness approaches, like those Tolle advocates, are acknowledged as a simple and effective way of dealing with anxiety and low mood. Here’s a really simple one, I often use when I realise I’m worrying too much about something. As I’m driving, I look at the three nearest cars for about two seconds and say what colour they are, in my mind.

I do this again when I realise I’ve drifted back into the worry that’s taking hold of me and want to snap out of it again. And then again and again. It’s about finding something else for my mind to latch on to, something in the here and now. But it’s about being aware in the first place that you need to let go of the thought.

Step Four – fix your relationships with other people.

Death fear impacts on not just our relationship with ourselves but those with other people. This is crucial because your death will involve other people. To be completely candid, no-one dies alone, even if at an emotional level they do. They are either in the bosom of family and kin or because they lack those networks, are dying within the community and hospital spaces our society has developed to ensure the vulnerable are looked after when they are ill and therefore, when they are dying.

Looking at death through the social lens means we ask the question “Who will be involved?” Which leads to “Who will be there?” That one is a very big question. Who will help us make domestic decisions? Who will do the practical things that we’d like done and who will sit with us in our last moments?

This means putting a bit of thought and preparation into these questions, say before we retire. It’s practical for the here and now, as well as the future.

And it will keep the relationships that matter most to us in good working order, which will nurture our psychological and spiritual health.

Build the relationships that resonate well for you.

This doesn’t mean bring more people into your life. It means do the psychological work to feel better about those around you. It may even mean detaching yourself from circles that don’t fulfil your emotional needs anymore.

When you are confronting death, you do not have to justify your behaviour to anyone. But ask practical questions about how you relate to people. This actually includes three different sets: service providers, family and friends and the person we want as our support person as we come to our end.

You will rely on someone to provide services for you. They might be a physiotherapist, or a nurse. They might be the person who brings food on a tray. Think about that person in particular. It is a humble task but one that will be provided either by a stranger, a friend or family member or the love of your life. This shows you that the people interacting with you at the end, will come from all aspects of life.

So now, how do I negotiate with them? When I’m feeling frightened and inconsolable, do I lash out at these people, allowing myself to project my anxieties on to them?

The truth is, we all do this, even if just a little bit. But as a general rule, people who’ve got this under control are happier. The people who have good relationships with family and friends, as a general rule, tend to have more supporters in the end stages. You’d be surprised by the high levels of people who die without loved ones around and in a state of clear loneliness.

It is easier to think about this, and develop skills to manage this, before the terminal diagnosis.

If you are in young middle age, is the person you live with intimately now, the person who you visualise being with you at the end? If they are not, can you change your domestic relationships? This doesn’t mean ending the relationship, but it might mean relating to them in a new way. And this is something you will have to lead and develop. You cannot rely on that other person to understand this unless you tell them.

Step Five – Learn about death.

This one is a very simple step. Learn to be in the presence of those who are dying. This will help you to prepare by giving you insights into what you will experience. It doesn’t mean seek out the dying. It means when people in your life are dying, stay connected with them, even if you are frightened.

Resources.

You can still follow sessions at the Lifting the Lid International online Festival. To find out more, go to:

https://hopin.com/events/liftingthelid/registration

Their talks and workshops will be available until the end of June, 2023.

A Good Death: A compassionate and practical guide to prepare for the end of life.

https://good-grief.com.au/a-good-death-book-margaret-rice/

Let’s Talk about it – an interview by Hilary Harper for ABC’s Life Matters.https://abcmedia.akamaized.net/rn/podcast/2019/05/lms_20190502_0906.mp3

https://good-grief.com.au/lets-talk-about-it/

Advice for future corpses and those who love them

By Sallie Tisdale

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/36373274-advice-for-future-corpses-and-those-who-love-them

Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now is a New York Times bestseller. It can be found at:

https://www.amazon.com/Power-Now-Guide-Spiritual-Enlightenment/dp/1577314808

Go to Good Grief’s section on advance care planning for more information on this.

https://good-grief.com.au/i-want-to-plan-a-good-death/

And to learn the important distinction between someone with no capacity and someone who could be described as vulnerable, go to our sponsored article: https://good-grief.com.au/sponsored-article-decision-making-is-a-human-right/