Sometimes, when someone is dying they just don’t want to focus on their disease any more. And during Covid-19, like many of the rest of us, the dying need a break from that too. That’s when a biography service for the dying can be just what the doctor ordered.

“We’ve found one of the things our clients really appreciate is the chance to be someone other than a patient with an illness. At a time in life when a lot of their meaningful activities have been taken from them, it’s wonderful for clients to be able to think of something else,” explained Robyn Swanson.

Robyn coordinates the Sacred Heart Community Palliative Care Team Biography Service at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, along with her co-worker Julie Gissing.

It’s not a medical model

“It’s not a medical model. It gives people their dignity back. Reflecting on the rich lives they have lived sometimes even helps them with their pain. It’s not just a distraction but it provides meaning,” said Julie.

So clients have the opportunity to meet and talk about their life as they put together a legacy document that will still be here when they are gone.

The biography service for the dying has 35 volunteers who are trained by the program. Over a period of usually five or six visits to the client’s home, the volunteer sits and listens to the person’s story. Having their story witnessed in that way is very therapeutic for the client.

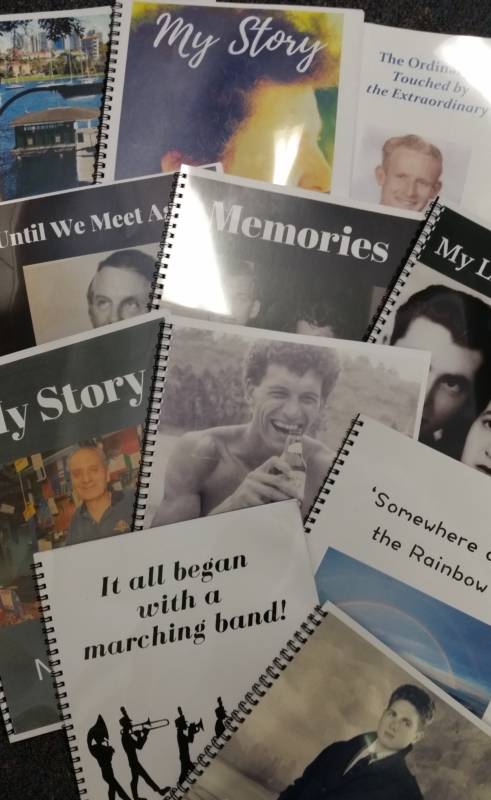

Two simple, bound, A4 sized paper copies are produced, with colour photographs. The biography is also placed on a USB stick, so that the family can have more copies printed if they want to. The service is funded by St Vincent’s Hospital bequests.

People share stories about who they are and what their lives have meant to them.

“We listen to their story to create these legacy documents. The story is always presented in the client’s voice, it’s in the first person, so when you read it when it’s finished, it has the voice of the client,” Julie said.

“Sometimes they reflect on their values, sometimes they have specific messages they want to share with family members. It’s really a matter for the client to decide what they want to say. The idea is that the biography always reflects what the client wants to say about themselves – not what we think they might want to say,” said Robyn.

“We give them time to reflect and it can take a while for people to process what they want to say about themselves,” she said.

Julie explained that for some people it might be the first opportunity they’ve had to share their story. And some people, can talk more easily about what they’ve done but have difficulty talking about their family or their feelings.

Our volunteers ‘hold the space’

“So our volunteers are trained to ‘hold the space’, they are listeners rather than interviewers,” she said.

With Covid-19, face to face visits are on hold. But the volunteers and clients are innovating, using technology to do their scheduled meetings. Some are sharing photos of themselves as a way of introducing themselves and then doing the interview by telephone.

“It’s never the same as being face to face with someone, a far speedier way of getting to know someone and build up trust. But we’ve found that both the volunteers and the clients have responded. And since there is no other way to do it, they’re making this work – and it still works, it’s very meaningful. In some cases, the volunteer and the client are splitting the weekly session into two, to make up for the limitations,” Julie said.

“We are hoping to be able to go back to how we provided the service before. But Covid-19 has opened us to the possibilities,” she said.

“One of the benefits of the Covid-19 crisis is that we have expanded our usual meeting schedule for the volunteers. We used to do a face-to-face meeting with the volunteers every six weeks but that has changed now to a Zoom meeting every fortnight. The volunteers really value the opportunity to talk to each other and to exchange ideas about how to improve their work,” Robyn said.

“Volunteers are saying ‘we are all going through this together’, let’s just help each other. And the volunteers are sharing information with each other about how to use the new technology,” she said.

Other examples

Work such as that done by the Sacred Heart Community Palliative Care Biography Service, with a therapeutic purpose at the end of life, is an expanding field of palliative care.

The St Vincents work is based on a model from New Zealand first developed by Ivan Lichter, former head of Te Omanga Hospice in New Zealand in 1990 and then adapted for volunteers by Jenny Kearney from Eastern Palliative Care in Melbourne in 2006.

Eastern Palliative Care https://epc.asn.au/ was the first to implement this model in Australia.

Another form of life review work was later developed in Canada, and it is called ‘dignity therapy’. This work was pioneered at the Manitoba Palliative Care Research Unit by Dr Harvey Max Chochinov.

“There is a distinction between our work and dignity therapy because we stress to our volunteers that they are not therapists, even though the work is therapeutic in the broader sense,” Julie said.

“It is a point of difference between our work and that of professional therapists taking someone through a therapeutic process,” she explained.

To find out more about Dr Chochinov’s work, go to Palliative Care Australia’s article: https://palliativecare.org.au/how-to-upload-patient-dignity-at-end-of-life

For information about other similar services in Australia, go to: https://palliativecare.org.au/talking-life-can-help-process-accepting-death

See also Reflections on Using Biographical Approaches in End-of-Life Care: Dignity Therapy as Example, by Olav Lindqvist, Guinever Threlkeld, Annette F. Street, et al at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1049732314549476

Good Grief! has over 300 articles. Read our latest with HIV educator David Polson on the changes to attitudes about HIV.

And for those who need support with grief: