(First published in the Good Grief May newsletter.)

While most Australians want to have control over their end-of-life, including not having life- prolonging treatment, still today, too few people empower themselves by taking the practical steps to make this happen.

Only 14 per cent of people over the age of 65 have filled in an advance care directive, the most effective way to get this control, estimates Advance Care Planning Australia, a national advice and support service funded by the Australian Government.

And if you’re someone who doesn’t want your life saved, you need to find a way to say this – there’s no point just muttering it to yourself or the television.

If you’re someone who doesn’t want your life saved, you need to find a way to say this – there’s no point just muttering it to yourself or the television.

You have to state it clearly, and in writing, and you have to make sure the person who’ll accompany you to hospital, cast as the ‘person responsible’, has not only heard what you’ve said but is taking it seriously. Because we all know that, paradoxically, the long-term spouse is less likely to hear the deep you than they are to hear what they expect the deep you to be.

‘But I said I didn’t want butter on my toast this time.’ ‘But you always have butter on you toast’ is irritating enough at breakfast time. To be misunderstood in your last days, when so much more is at stake, takes the opportunity to be unheard or misinterpreted to a completely new level.

You have the right to say no to every intervention

You have the right to say no to every intervention and treatment that is offered to you – even antibiotics in the fairly predictable scenario of you catching this year’s flu and it turning into pneumonia.

We know of an elderly woman who repeatedly said she didn’t want to be treated with antibiotics if she ended up with pneumonia. Sure enough, she ended up in the Accident & Emergency ward of a busy hospital. It was only because her son was a doctor, taking the responsibility for the decision from his peers, that he could negotiate for her not to have that intervention. She died at that time, as she wished, not having to return to a life she had clearly expressed no desire for.

But very few of us have the persuasive doctor son, ready to take on the system, and standing at our side when we need him. In that type of emergency the rest of us would have relatives who’ve been ordered to sit outside until the crisis is over, when the first dose of antibiotics has already been administered.

Very few of us have the persuasive doctor son, ready to take on the system, and standing at our side when we need him

It’d be quite reasonable to say that of 100 parallel episodes playing out across the country today, like the one involving the doctor son, less than 10 of the people involved will get their wish not to be treated.

So the voice of the old person in hospital, infantilised by our society anyway, and further made incomprehensible and weakened because of illness, will not be heard. A written, appropriately witnessed document is needed.

In most Australian states it has to be written on the just-so legally accepted document and the lack of the correct legal documentation is one of the most likely reasons for it to be rejected, according to Advance Care Planning Australia.

In NSW an advance care directive can be written on the back of an envelope and still be legally binding because this is protected by Common Law. But the reality is, despite this, the casual formats are often ignored. So its Common Law strength – that it’s not outlined in Statutes – is also its weakness.

This is the reason one lawyer who contacted us recently says he always uses the NSW Health advance care directive form.

People tend to see advance care planning as something for old people. Yet one third of Australians will die before the age of 75, according to Advance Care Planning Australia.

Merran Cooper supported her husband to have a good death when she was only 24. So it was absolutely bewildering to her that more than 30 years later, working as a new doctor in hospitals, that she saw so many deaths done badly.

Six times a shift

“Six times a shift, I’d be presented with someone who’d lost the capacity to speak, usually because of dementia or who was very unwell and had deteriorated suddenly,” explained Merran.

She noted all the reasons why the forms people gave her were useless. For example, the directive might have been left behind in the ambulance, illegible or unable to be found by relatives.

And such documents aren’t necessarily automatically accepted by hospital staff, even though education of hospital staff about them is occurring more effectively today. Often, these staff face the scenario where they believe the best thing is to let a patient die, without any intervention, but there is a large group of distressed relatives just outside the door, getting the message across emphatically, to go to any lengths to save the patient’s life, no matter how unachievable this may be.

This led Merran to the conclusion that the advance care directives we typically rely on in modern hospitals in Australia: “Are just simply not fit for purpose because there are so many broken links in the chain of communication.”

Merran decided to do something about all of this, and in 2018 started Touchstone Life Care, a digital advance care directive service to leap-frog over all the problems.

It’s one of many new directions that advance care directives are taking, like financial and legal planning generally. In fact, we’re being invited to digitise just about everything these days.

Ideally these innovative, technology driven changes to services, will bring about the revolution needed to make advance care directives more widely accessible, easy to use and universal.

The Covid-19 pandemic helped speed up the process of hospitals sorting out which situations were ideal for expanding communication technology, such as telehealth, and which were not.

Their solutions provided powerful evidence that communication technology, rather than being the enemy of human emotion and experience, can enhance it considerably.

while end-of-life is not the right moment for intrusive technology, the most important part of the end-of-life discussion – the communication of the advance care plan – is ideal for it.

And while end-of-life is not the right moment for intrusive technology, the most important part of the end-of-life discussion – the communication of the advance care plan – is ideal for it. Because there are two major problems in advance care directives today.

The first is confusion over whether this is the ‘real’ document: has another one superseded it, is the one the son is holding the right one or the one the daughter is holding? If there’s a fight going on about this, and there often is, then both versions of the document have no credibility.

The second common problem is the practical question: where is it? In the third drawer down in the desk in the den? With the solicitor – what is her number? With the GP – who is the GP?

Today, these documents can now be scanned and stored centrally. Sometimes this is done with the best of intentions in the comms system at a nursing home, often the place of residence of the person being transported to the hospital.

But this isn’t particularly useful. The document can still be overridden and the ambulance called to take the person to hospital where treatment for total recovery will be the objective. And if the care staff on duty that night want to read the advance care directive, they often don’t have access to the computer. If they want to send it in the ambulance, they don’t have access to the printer.

Add to this, in NSW, the role of the ambulance service currently causes extra confusion rather than clarity.

Until last year, an ambulance care plan, separate to the advance care directive, had to be lodged with the ambulance service. This didn’t cover people residing in nursing homes, the places most likely to need the direction.

But since last year, NSW Ambulance has been reviewing the system, directing ambulance care workers to refer to the advance care directive and not the ambulance plan. The result? In many cases the ambulance service will make its own decision to resuscitate, regardless of what the paperwork says.

We don’t believe it’s acceptable that this review has taken at least a year. Clarity is needed and its needed now.

Innovations in record keeping

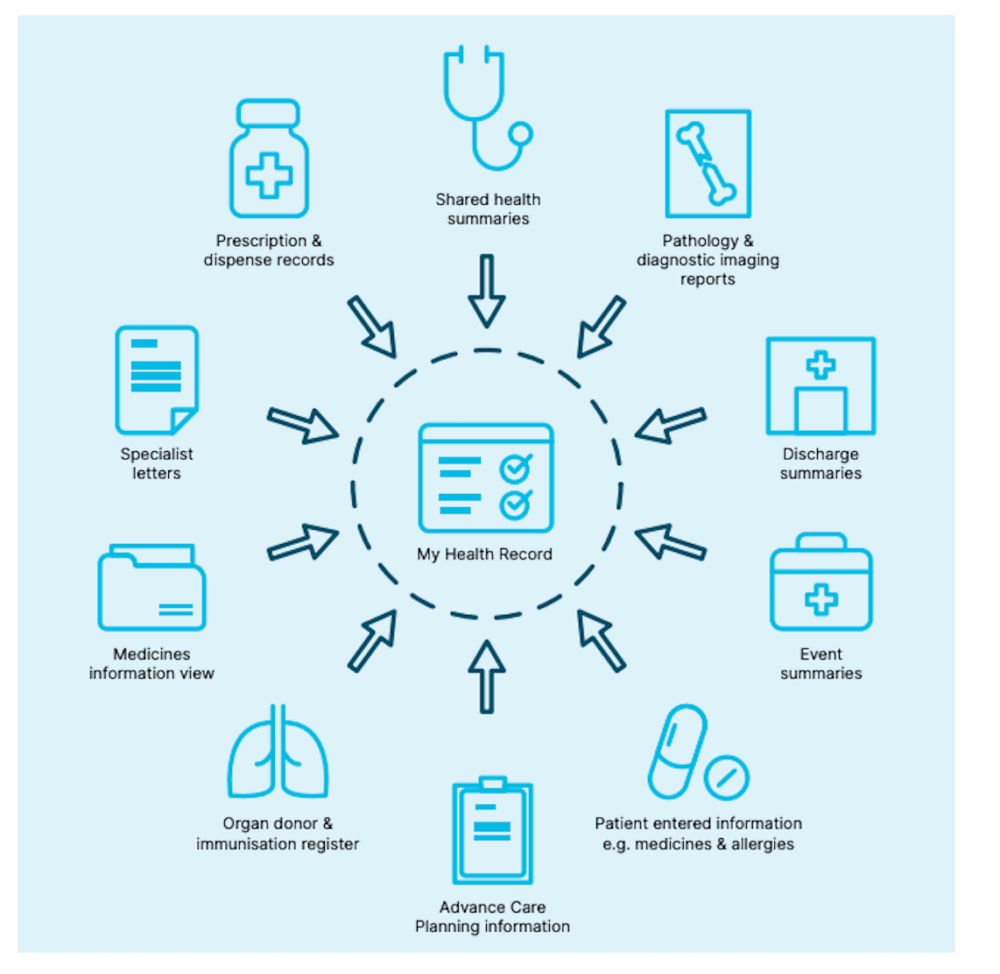

All of the above are the reasons why current innovations in record keeping are coming into their own, starting with the backbone, Australia’s My Health Record system a national e-record system for medical records. This has a function which includes storage of advance care directives. And if the above mentioned nursing home uploads it to this system, rather than hugging it in its own, then that becomes very useful and can counteract most of the other problems mentioned.

My Health Record generated a flurry of fear about privacy issues when it was first introduced in 2016. Some of these concerns were legitimate. Some people were quite reasonably concerned that if sensitive documents such as mental health records were accessed by the wrong people, say potential employers, that this could have damaging consequences. We understand that those privacy concerns have been addressed.

But as we age, the more complex our medical records become. We have to weigh up our fears of them getting into the wrong hands, against the risk that they won’t get into any hands at all.

When you see your lawyer about your will, this is a good moment to discuss your advance care planning, even though this is about medical circumstances. Discussion of your advance care plan will also involve discussing your enduring medical guardian. This is something that requires a signature that has to be witnessed, usually by a lawyer.

For your convenience, lawyers handling the enduring guardianship will often place an advance care directive with those documents. Ask for these to be updated to your e-record.

Advance care directives are now being promoted vigorously through programs such as ELDAC (End of Life Directions for Aged Care), a national consortium of universities and hospitals.

You can decide to work with a private service such as Merran’s Touchstone Life Care. The special advantage of this is that these practitioners have lots of experience and, unlike ELDAC which only gives advice, these services take responsibility for completing the directive for you, for a fee.

‘Safe Space’ workshops

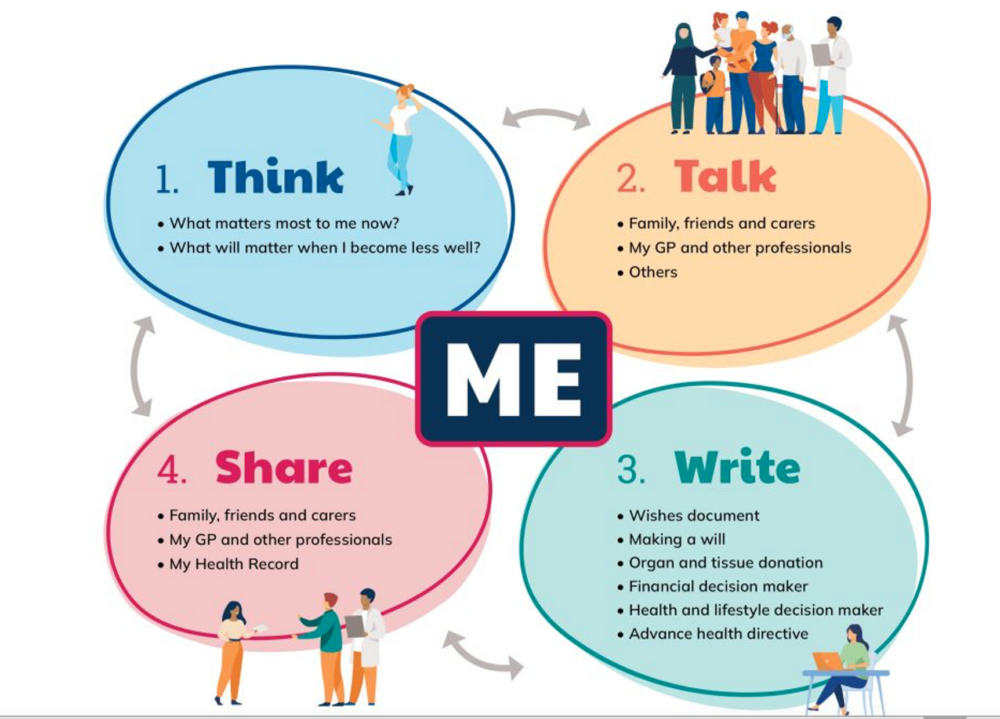

The development of digital advance care documents doesn’t detract from the need for discussions, particularly with family and or those who will care for you at the end of life.

And this process might involve thinking and talking to others outside the family.

Palliative Care WA has a series of workshops on advance care planning which it is currently advertising on its Events page.

Among these is it’s ‘Safe Space’ online workshops.

“They are only open to people with a chronic condition or terminal illness, as well as those who care for family or friends with a chronic condition or terminal illness,” it says.

“While the core information is the same as our other workshops, we recognise that some people feel more comfortable sharing questions and concerns with those in similar circumstances… within a ‘safe space’.”

“We have one of our safe space online workshops coming up soon on Wednesday June 1.

For more information about these, go to:

Resources

For more about Touchstone Life Care go to: https://touchstonelifecare.com/

Want to hear more from us? Sign up to the Good Grief newsletter.

For those who want to do their advance planning through different language groups and in way sensitive to their own culture, the Multicultural Communities Council of Illawarra has developed a multi-language sheet with contact points. They are a non-profit charity that supports people and communities from culturally and linguistically (CALD) diverse backgrounds in the Illawarra/ Shoalhaven, and ACT/ Queanbeyan regions.

For information about advance care planning and the law, go to:

https://www.advancecareplanning.org.au/law-and-ethics/advance-care-planning-and-the-law

To see a powerful video about advance care planning

A patient who doesn’t have legal capacity because of dementia, even the early signs of it, can’t sign documents such as wills and the assigning of their power of attorney. But they can still make some crucial decisions.

See our story published on June 22, 2020, on advance care planning and dementia patients.

For more on ambulance care plans and current problems in NSW.